BAFTA Responds to Criticism for Snubbing Female Directors in the Nomination

Variety.com: British Academy comes under fire for female directors snub but says it reflects a wider industry problem

“Male, pale and stale” – that was the sentiment among some commentators in print and online Wednesday after the newly announced BAFTA nominations exhibited a lack of gender and ethnic diversity in the awards’ most prominent categories.

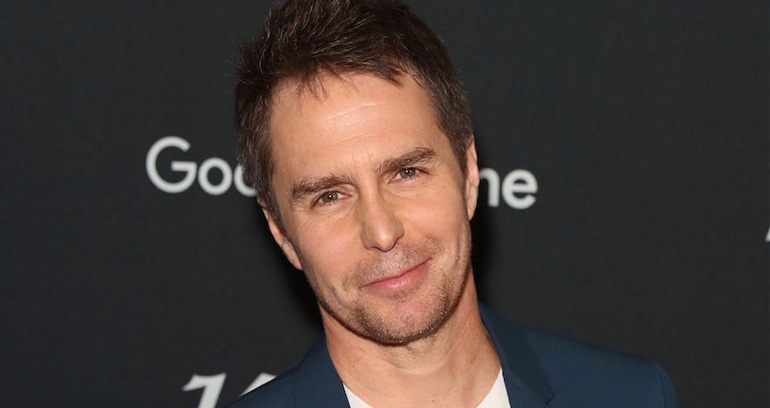

Only two of the 20 actors and actresses nominated for their performances were not white. The most notable absence, however, was of women in the best-director category, especially coming off of the all-male shortlist at the Golden Globes in the same category and the snubs for the likes of Greta Gerwig (pictured) and Patty Jenkins. No woman has received a BAFTA nomination for director since 2013.

Veteran British film critic Peter Bradshaw said that the lack of a female presence in the category betrayed the #MeToo message. The Women Film Directors Twitter account also drew attention to the female-free shortlist, and noted that the few women who have been nominated in the category over the years have all been white. The same is true of the Oscars.

BAFTA Chair Jane Lush, who had opened Tuesday’s nominations press conference by expressing her organization’s backing for moves to redress imbalances in the industry, told Variety that the lack of female director nominees was the result of a systemic problem.

“Of course we want to see women in the best director category. It is a reflection of the industry to a certain extent and we should be doing something about it, and that’s why we have BAFTA Elevate,” Lush said, referring to a program designed to promote female directors’ careers. “It’s not about blaming people. It’s about what can we do to make it different.”

BAFTA said that just 16% of the entries in the director category were women. Since the advent of the best-director award in 1968, women have been nominated in the category only seven times, and two of those were for Kathryn Bigelow, still the only woman to walk away with the award, for “The Hurt Locker” in 2010.

“It’s a much bigger issue than BAFTA or the Golden Globes,” said Kate Kinnimont, chief executive of Women in Film & TV. “It’s more about the culture we live in than a particular festival or organization. If there are only 7% of women directing films, then if you are choosing five, the chances of [nominations] are slim. It’s really about how women are perceived on the business side.”

Kinnimont’s group is working with BAFTA and the British Film Institute on new industry guidelines on harassment, which should be published within weeks. BAFTA has also attempted to broaden its membership, which is thought currently to be about 40% female. New criteria for the categories of outstanding British film and outstanding debut by a British writer are also coming, with eligibility restricted to movies that fulfill the BFI’s diversity standards.

There were, however, calls for further change off the back of the nominations. “It is disappointing to see that women directors are being overlooked, yet again,” Susanna White, chair of the Directors U.K. Film Committee and the director of “Woman Walks Ahead” and “Generation Kill,” said in a statement issued to Variety.

“The ‘Best Director’ nominations are the result of votes of the BAFTA members,” White added. “When the outcome of that vote is so skewed as to exclude the great work of women directors, you have to look at the voting systems of the Awards bodies and the demographic make-up of their membership, as they are clearly not representative of the industry.“

Expanding the number of nominations in various categories is another possible solution, but is not on the agenda, insiders said, citing concerns that the awards ceremony would become unwieldy with eight or nine nominations per category.

“There are only five nominees. I loved ‘Lady Bird’ and it is a very well-directed

“Male, pale and stale” – that was the sentiment among some commentators in print and online Wednesday after the newly announced BAFTA nominations exhibited a lack of gender and ethnic diversity in the awards’ most prominent categories.

Only two of the 20 actors and actresses nominated for their performances were not white. The most notable absence, however, was of women in the best-director category, especially coming off of the all-male shortlist at the Golden Globes in the same category and the snubs for the likes of Greta Gerwig (pictured) and Patty Jenkins. No woman has received a BAFTA nomination for director since 2013.

Veteran British film critic Peter Bradshaw said that the lack of a female presence in the category betrayed the #MeToo message. The Women Film Directors Twitter account also drew attention to the female-free shortlist, and noted that the few women who have been nominated in the category over the years have all been white. The same is true of the Oscars.

BAFTA Chair Jane Lush, who had opened Tuesday’s nominations press conference by expressing her organization’s backing for moves to redress imbalances in the industry, told Variety that the lack of female director nominees was the result of a systemic problem.

“Of course we want to see women in the best director category. It is a reflection of the industry to a certain extent and we should be doing something about it, and that’s why we have BAFTA Elevate,” Lush said, referring to a program designed to promote female directors’ careers. “It’s not about blaming people. It’s about what can we do to make it different.”

BAFTA said that just 16% of the entries in the director category were women. Since the advent of the best-director award in 1968, women have been nominated in the category only seven times, and two of those were for Kathryn Bigelow, still the only woman to walk away with the award, for “The Hurt Locker” in 2010.

“It’s a much bigger issue than BAFTA or the Golden Globes,” said Kate Kinnimont, chief executive of Women in Film & TV. “It’s more about the culture we live in than a particular festival or organization. If there are only 7% of women directing films, then if you are choosing five, the chances of [nominations] are slim. It’s really about how women are perceived on the business side.”

Kinnimont’s group is working with BAFTA and the British Film Institute on new industry guidelines on harassment, which should be published within weeks. BAFTA has also attempted to broaden its membership, which is thought currently to be about 40% female. New criteria for the categories of outstanding British film and outstanding debut by a British writer are also coming, with eligibility restricted to movies that fulfill the BFI’s diversity standards.

There were, however, calls for further change off the back of the nominations. “It is disappointing to see that women directors are being overlooked, yet again,” Susanna White, chair of the Directors U.K. Film Committee and the director of “Woman Walks Ahead” and “Generation Kill,” said in a statement issued to Variety.

“The ‘Best Director’ nominations are the result of votes of the BAFTA members,” White added. “When the outcome of that vote is so skewed as to exclude the great work of women directors, you have to look at the voting systems of the Awards bodies and the demographic make-up of their membership, as they are clearly not representative of the industry.“

Expanding the number of nominations in various categories is another possible solution, but is not on the agenda, insiders said, citing concerns that the awards ceremony would become unwieldy with eight or nine nominations per category.

“There are only five nominees. I loved ‘Lady Bird’ and it is a very well-directed